I recently got my eight-year old daughter a Bible and she's been reading it from the beginning. Last night, she was in her room reading when she came across the heading of the story of the Passover. She came out and asked if she should read that part.

"Why wouldn't you?" I asked.

"Isn't it a Jewish story?" she replied.

Oy! What happened? We've talked about Passover before. I love Passover, and I've tried to convey to her my great respect for the Jewish rituals and traditions, but apparently what she got out of it was, "That's Jewish, not Christian." And then to think that maybe she shouldn't even read the story -- wow!

Of course, it was a great "teachable moment" as they say. I went to the Bible with her, put my thumb in Genesis 1 and my index finger in the middle of Acts and said, "That much of the Bible is a Jewish story." And we talked about Jesus being Jewish and the early Christians being Jewish and how really the whole Bible is Jewish and so on.

It's just a bit disturbing how natural it seems to be to put up boundaries. It's no wonder prejudice is so easily passed on from generation to generation.

Monday, February 27, 2006

Sunday, February 26, 2006

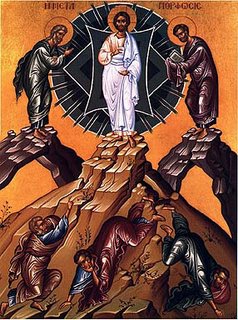

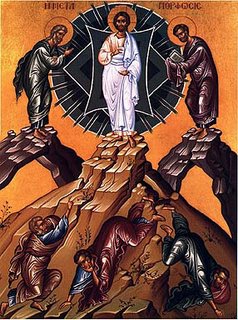

After Six Days

Anyone who's read even a little bit of Mark's gospel knows that in this gospel everything happens "immediately." Well, almost everything.... In the gospel reading from this Sunday, while expecting Mark's typical announcement of immediacy, I was jarred a bit by the opening words: "After six days..." (REB)

I have a theory about Mark's gospel. In Mark 1:3, we read Mark's quotation of Isaiah, "The voice of one crying out in the wilderness: "Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight.'" The word translated "straight" here is the Greek word "euthus." It appears 60 times in the New Testament, 41 of those times in Mark. Guess how it's usually translated -- "immediately"!

So this is my theory. This quotation from Isaiah serves as Mark's keynote speech. From then on, whenever Mark uses the word "euthus" ("immediately"), he is pointing to an example of how the paths of the Lord are being made straight. In current theological jargon, we'd call these instances of the kingdom of God breaking in -- the "already" of the Gospel.

But the Gospel, we are told, also contains a measure of "not yet." And this is where the "six days" in Mark 9:2 comes in. Perhaps "six days" represents God's work of creation before the day of rest (not yet into an eighth day theology?), but, in any event, it's not immediately, not yet. It's more than a little bit ironic, because the Transfiguration is obviously the most visible example of the kingdom "breaking in" in the Gospel. But it's just a hint -- a foretaste of the feast to come.

Already, we experience the kingdom of God. We see God's liberation being worked in the world. The blind see, the lame walk and the poor have good news preached to them. But this is just the first fruits. The Transfiguration gives us a peek at the fullness of the harvest.

I have a theory about Mark's gospel. In Mark 1:3, we read Mark's quotation of Isaiah, "The voice of one crying out in the wilderness: "Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight.'" The word translated "straight" here is the Greek word "euthus." It appears 60 times in the New Testament, 41 of those times in Mark. Guess how it's usually translated -- "immediately"!

So this is my theory. This quotation from Isaiah serves as Mark's keynote speech. From then on, whenever Mark uses the word "euthus" ("immediately"), he is pointing to an example of how the paths of the Lord are being made straight. In current theological jargon, we'd call these instances of the kingdom of God breaking in -- the "already" of the Gospel.

But the Gospel, we are told, also contains a measure of "not yet." And this is where the "six days" in Mark 9:2 comes in. Perhaps "six days" represents God's work of creation before the day of rest (not yet into an eighth day theology?), but, in any event, it's not immediately, not yet. It's more than a little bit ironic, because the Transfiguration is obviously the most visible example of the kingdom "breaking in" in the Gospel. But it's just a hint -- a foretaste of the feast to come.

Already, we experience the kingdom of God. We see God's liberation being worked in the world. The blind see, the lame walk and the poor have good news preached to them. But this is just the first fruits. The Transfiguration gives us a peek at the fullness of the harvest.

Tuesday, February 21, 2006

The Invisible Things of God

Thomas Adams at Without Authority has put up some good posts recently on the subject of natural theology. Most recently he has undertaken to swim the heady waters of the debate as it flowed between Brunner, Barth and Tillich. But me, I'm Old School, so I thought I'd offer some thoughts from Luther.

Given the extended nature of my comments, it seemed best to me to chime in here and not just in the comments there (but do check out Thomas' blog for some good theological reflection).

Luther touches on a point that seems to me to be relevant to the Brunner-Barth debate in his 1518 Heidelberg Disputation (my favorite of Luther's works). In thesis 19 he says:

Luther's proof above raises an interesting parallel to Abraham Heschel's thoughts on the message of the prophets. Heschel maintains that the prophets have no intention of expounding the value of abstract ideals which God happens to possess as attributes. The prophets do not wish to educate us about "virtue, godliness, wisdom, justice, goodness, and so forth." Rather, they wish to introduce us to a God whose nature is manifested in virtue, justice, goodness, and so forth. Their primary intention is that we know God, not that we know God's attributes.

And this, I think, is the sought after "point of contact." The point of contact is the God who comes down, the God who comes to us in the world. In vain do we search for God in human things. Nevertheless, in human things God comes to us. We may meet God in relationship but never in analytic inquiry.

Given the extended nature of my comments, it seemed best to me to chime in here and not just in the comments there (but do check out Thomas' blog for some good theological reflection).

Luther touches on a point that seems to me to be relevant to the Brunner-Barth debate in his 1518 Heidelberg Disputation (my favorite of Luther's works). In thesis 19 he says:

That person does not deserve to be called a theologian who looks upon the invisible things of God as though they were clearly perceptible in those things which have actually happened.Other translations read "created things" in place of "those things which have actually happened." Now, on the face of it, this seems to be a direct contradiction of St. Paul in Romans 1:20 ("Ever since the creation of the world his invisible nature, namely, his eternal power and deity, has been clearly perceived in the things that have been made."), but it is clear from Luther's "proof" that he is intentionally going for shock value. His proof states:

This is apparent in the example of those who were "theologians" and still were called fools by the Apostle in Rom. 1[:22]. Furthermore, the invisible things of God are virtue, godliness, wisdom, justice, goodness, and so forth. The recognition of all these things does not make one worthy or wise.So, it would seem that Luther grants a "point of contact" in nature, such that God may be perceived in nature (or in "those things that have actually happened"), but he maintains, on the authority of the apostle, that we would be fools to seek to know God that way. When we seek to know God that way, we are seeking the "naked God", as Luther says, rather than God clothed in his promises. What we find may lead us to knowledge about God, but we will never meet God in such a way and certainly not know God.

Luther's proof above raises an interesting parallel to Abraham Heschel's thoughts on the message of the prophets. Heschel maintains that the prophets have no intention of expounding the value of abstract ideals which God happens to possess as attributes. The prophets do not wish to educate us about "virtue, godliness, wisdom, justice, goodness, and so forth." Rather, they wish to introduce us to a God whose nature is manifested in virtue, justice, goodness, and so forth. Their primary intention is that we know God, not that we know God's attributes.

And this, I think, is the sought after "point of contact." The point of contact is the God who comes down, the God who comes to us in the world. In vain do we search for God in human things. Nevertheless, in human things God comes to us. We may meet God in relationship but never in analytic inquiry.

Monday, February 20, 2006

Thursday, February 16, 2006

Through the Roof

The opening line of this week's gospel reading is very curious. It says, "When he returned to Capernaum after some days, it was reported that he was at home" (emphasis added).

I've never thought of Jesus as having a home during the time of his ministry, and this story in particular I've always thought to have taken place in Peter's home. Yet there it is. The New Jerusalem translation won't believe it, and translates this phrase as "he was in the house", but Mark 3:19 also talks about Jesus going home, and Matthew 4:13 says he made his home in Capernaum.

John's gospel, as always, offers a more enticing and less direct look at this. In John 1:38, Andrew and "the other disciple" ask Jesus, "Where are you staying?" Jesus answers, "Come and see."

Now you may be wondering, why am I laboring this point? Surely, Jesus was constantly traveling during his ministry and where his home was is little more than trivia, right? But there's a certain symbolic significance to where Jesus' home is. John's gospel points to this. Where Jesus is staying (abiding), there is the kingdom of heaven.

So this gives a little extra something to Mark's mention that "he was at home." In Mark 1:10 we heard that when Jesus was baptized "he saw the heavens torn apart" and the Spirit descended. Now, in the story that follows, people seeking Jesus dig through the roof to get to him. It's an interesting parallel.

We often talk about Jesus' Incarnation in terms of the kingdom of heaven "breaking in" and there's no better picture of that than the heavens being "torn apart" at his baptism. But in this Sunday's reading from Mark's gospel, we get another picture of the kingdom of heaven "breaking in" only this time it is people coming to Jesus.

I've never thought of Jesus as having a home during the time of his ministry, and this story in particular I've always thought to have taken place in Peter's home. Yet there it is. The New Jerusalem translation won't believe it, and translates this phrase as "he was in the house", but Mark 3:19 also talks about Jesus going home, and Matthew 4:13 says he made his home in Capernaum.

John's gospel, as always, offers a more enticing and less direct look at this. In John 1:38, Andrew and "the other disciple" ask Jesus, "Where are you staying?" Jesus answers, "Come and see."

Now you may be wondering, why am I laboring this point? Surely, Jesus was constantly traveling during his ministry and where his home was is little more than trivia, right? But there's a certain symbolic significance to where Jesus' home is. John's gospel points to this. Where Jesus is staying (abiding), there is the kingdom of heaven.

So this gives a little extra something to Mark's mention that "he was at home." In Mark 1:10 we heard that when Jesus was baptized "he saw the heavens torn apart" and the Spirit descended. Now, in the story that follows, people seeking Jesus dig through the roof to get to him. It's an interesting parallel.

We often talk about Jesus' Incarnation in terms of the kingdom of heaven "breaking in" and there's no better picture of that than the heavens being "torn apart" at his baptism. But in this Sunday's reading from Mark's gospel, we get another picture of the kingdom of heaven "breaking in" only this time it is people coming to Jesus.

Monday, February 13, 2006

Easy Answers

"In the realm of theology, shallowness is treason."

-Abraham Heschel, The Prophets

Is there a principle more consistently violated in American Christianity than this? The opposite principle seems more often to be observed -- if you can't get your theology on a bumper sticker, it's too complex.

I know there's good theology out there. It's the thing that drives my faith. I don't want answers to theological questions. I want to know God. Often people act as though that isn't the business of theology, but I can't imagine what else it's good for.

And yet, there's a certain paradox here. The most basic questions of religion must, if we are honest, remain unanswerable. Does God exist? Popular religion will answer with a quick "Yes" and probably follow it up with a simple logical proof. After all, if we can't even answer that question, our faith is surely exposed as a scam, right?

But if we invoke Heschel's principle here, "in the realm of theology, shallowness is treason," it becomes evident that we should not give a quick and easy answer to the question of God's existence. It's something we have to wrestle with. Our wrestling may presume an answer. It may seek to redefine the question. But it cannot pretend that it's an easy question.

The same is true of Christ's question, "Who do you say that I am?" The same is true of all the most basic questions of the faith: "What do we mean by salvation?" "How does the death of Christ accomplish salvation?" "What do we mean by 'heaven'?"

Easy answers are the enemy of true faith.

-Abraham Heschel, The Prophets

Is there a principle more consistently violated in American Christianity than this? The opposite principle seems more often to be observed -- if you can't get your theology on a bumper sticker, it's too complex.

I know there's good theology out there. It's the thing that drives my faith. I don't want answers to theological questions. I want to know God. Often people act as though that isn't the business of theology, but I can't imagine what else it's good for.

And yet, there's a certain paradox here. The most basic questions of religion must, if we are honest, remain unanswerable. Does God exist? Popular religion will answer with a quick "Yes" and probably follow it up with a simple logical proof. After all, if we can't even answer that question, our faith is surely exposed as a scam, right?

But if we invoke Heschel's principle here, "in the realm of theology, shallowness is treason," it becomes evident that we should not give a quick and easy answer to the question of God's existence. It's something we have to wrestle with. Our wrestling may presume an answer. It may seek to redefine the question. But it cannot pretend that it's an easy question.

The same is true of Christ's question, "Who do you say that I am?" The same is true of all the most basic questions of the faith: "What do we mean by salvation?" "How does the death of Christ accomplish salvation?" "What do we mean by 'heaven'?"

Easy answers are the enemy of true faith.

Friday, February 10, 2006

Thought and Touch

"Thought is like touch, comprehending by being comprehended."

-Abraham Heschel

I put this up without comment earlier in the week. I was intimidated by it and didn't know if I could do it justice with commentary. I'm still not sure that I can, but I just can't pass it by. When I first read this, it puzzled me. I had no idea what it meant, but it was short and pithy enough to get a hook in my brain, so I thought about it.

For starters, how can "touch" be described as "comprehending by being comprehended"? In what way does what I touch comprehend me? On a personal level, I can't touch someone without alerting them to my presence. Touch can't be secret. And it's two-way communication. The one who touches is simultaneously touched. In the language of Martin Buber, who like Heschel was a Hasidic Jew, touch is an inherently "I-you" sense. Even as I touch a rock, the rock touches me.

And Heschel suggests that thought is like this also. I can have no direct contact with an idea. When it enters my mind, I perceive only by allowing it to interact with my mind. It must become a part of the fabric of my thought-world.

It is now a well-recognized fact that there is no such thing as an objective observer. All of my observations are colored and shaped by my prior biases and expectations. In scientific language, the observer modifies the outcome of any experiment. What is less commonly reflected upon is that the observer is affected by the experiment.

At this point, we as hearers have some degree of choice. We are able to decide, to some degree, how much we will allow what we hear to impact us and how much we will exert our own influence on the incoming idea. The more precisely I fit an idea into my existing mental framework, the less impact it will have upon that framework. Alternatively, I can choose to receive the word, to hear it as something new. I allow the word to address me. In so doing, I comprehend by being comprehended.

-Abraham Heschel

I put this up without comment earlier in the week. I was intimidated by it and didn't know if I could do it justice with commentary. I'm still not sure that I can, but I just can't pass it by. When I first read this, it puzzled me. I had no idea what it meant, but it was short and pithy enough to get a hook in my brain, so I thought about it.

For starters, how can "touch" be described as "comprehending by being comprehended"? In what way does what I touch comprehend me? On a personal level, I can't touch someone without alerting them to my presence. Touch can't be secret. And it's two-way communication. The one who touches is simultaneously touched. In the language of Martin Buber, who like Heschel was a Hasidic Jew, touch is an inherently "I-you" sense. Even as I touch a rock, the rock touches me.

And Heschel suggests that thought is like this also. I can have no direct contact with an idea. When it enters my mind, I perceive only by allowing it to interact with my mind. It must become a part of the fabric of my thought-world.

It is now a well-recognized fact that there is no such thing as an objective observer. All of my observations are colored and shaped by my prior biases and expectations. In scientific language, the observer modifies the outcome of any experiment. What is less commonly reflected upon is that the observer is affected by the experiment.

At this point, we as hearers have some degree of choice. We are able to decide, to some degree, how much we will allow what we hear to impact us and how much we will exert our own influence on the incoming idea. The more precisely I fit an idea into my existing mental framework, the less impact it will have upon that framework. Alternatively, I can choose to receive the word, to hear it as something new. I allow the word to address me. In so doing, I comprehend by being comprehended.

Tuesday, February 07, 2006

Biblical Relevance

A student of philosophy who turns from the discourses of the great metaphysicians to the orations of the prophets may feel as if he were going from the realm of the sublime to the arena of trivialities. Instead of dealing with the timeless issues of being and becoming, of matter and form, of definitions and demonstrations, he is thrown into orations about widows and orphans, about the corruption of judges and affairs of the market place. Instead of showing us a way through the elegant mansions of the mind, the prophets take us to the slums.One of the standard criticisms brought against Christianity is that it is a "pie-in-the-sky-by-and-by" religion. But curiously, one of the chief obstacles people, specifically Christians, have in developing a love for the Bible is that it lacks what I may call, for lack of a better term, spiritual profundity. It isn't awe-inspiring in the way, for example, that the Tao Te Ching or the Upanishads can be. It's too earthy.

-Abraham Heschel, The Prophets

Members of my family, knowing my love for the Bible, will occaissionally ask me to read them something they'll like, by which I take them to mean something that they'll hear and say, "Ah, yes! That's beautiful!" I invariably respond with selected bits of Romans 8 or Isaiah 40, and they are satisfied. But if they later pick up a Bible themselves looking for such inspirations, they'll quickly put it back down.

Heschel says that he turned from the study of philosophy to the study of the prophets because "philosophy had become an isolated, self-subsisting, self-indulgent, entity.... The answers offered were unrelated to the problems." Ironically, this sounds a lot like what people seem to want from the Bible. They would rather it were a book of platitudes than what it is.

I think this has to do with our cultural understandings of what a "Holy Book" should be. If God were to speak to us, it would sound like Bach's "Mass in B Minor", right? Everyone in western culture can sigh with pleasure when they hear, "he is named Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace," but we're left scratching our heads when we hear, "Therefore I am like maggots to Ephraim, and like dry rot to the house of Judah" (Hosea 5:12).

Could it be that we want a God who is a little less relevant to daily life?

Monday, February 06, 2006

Wallis and Bonhoeffer

I just read today's SoJo mail which features a piece by Jim Wallis on the importance of Bonhoeffer. This is promoting tonight's PBS showing (10 EST) of Martin Doblmeier's excellent documentary on Bonhoeffer (not to be missed).

There's a natural synergy between Wallis' Sojourners movement and Bonhoeffer's theology -- both are all about the relationship of faith to the world around us, but I'm afraid I've been getting a little weary of Wallis' rhetoric lately, and I think this piece helped me see why. When I first read Wallis' God's Politics it really struck a chord with me. Here was a solid presentation of a politics of peace and social justice that I could get behind. But as the months have passed, I see less and less difference between the weekly e-mails I get from Sojourner's and the weekly e-mails I get from the Democratic commitee -- both are coming across as bald-faced propaganda, and even though it's propaganda for the side I support, it strikes a sour note with me.

Now here's where Wallis' essay struck me. As he's describing Bonhoeffer's theology, he says this:

This is what I mean -- in the statement above, I take "believing in Jesus" to be the evangelical/Baptist "accepting Jesus as my Savior" kind of profession of faith, and I take Wallis to be acknowledging that it is needed. Then, in supposed agreement with Bonhoeffer, he says that to this must be added acts of obedience. The problem I have with this, theologically, is that it amounts to cheap grace plus works of the law with no inidication of what it is that this latter was necessary for other than congruency.

The genius of Bonhoeffer is precisely in his presentation of obedience to Christ as the very susbtance of faith, not something done in addition to it. It is precisely as God is redeeming in Christ the world that we are called to take up the yoke of Christ. In this regard, Bonhoeffer cites Matthew 11:28-30 ("Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.") at the end of his introduction to Discipleship.

So, to be clear, the issue I have with Jim Wallis is not with his cause. I support his cause and I thank God for calling him to this work. This issue I have, increasingly, is with his presentation, which far too often draws on the clumsy tool of Law where it could invoke the power of the Gospel.

There's a natural synergy between Wallis' Sojourners movement and Bonhoeffer's theology -- both are all about the relationship of faith to the world around us, but I'm afraid I've been getting a little weary of Wallis' rhetoric lately, and I think this piece helped me see why. When I first read Wallis' God's Politics it really struck a chord with me. Here was a solid presentation of a politics of peace and social justice that I could get behind. But as the months have passed, I see less and less difference between the weekly e-mails I get from Sojourner's and the weekly e-mails I get from the Democratic commitee -- both are coming across as bald-faced propaganda, and even though it's propaganda for the side I support, it strikes a sour note with me.

Now here's where Wallis' essay struck me. As he's describing Bonhoeffer's theology, he says this:

Believing in Jesus was not enough, said Bonhoeffer. We were called to obey his words, to live by what Jesus said, to show our allegiance to the reign of God, which had broken into the world in Christ.Far be it from any Lutheran, Bonhoeffer included, to say that believing in Jesus is not enough. Granted, Wallis doesn't speak Lutheranese. Even so, in a strict parsing of his statement above, it seems to me that precisely what is missing is faith. I don't mean to imply that Wallis isn't a man of faith -- I'm certain he is -- but his evangelical roots are showing here and it makes the rhetoric a little rough going down.

This is what I mean -- in the statement above, I take "believing in Jesus" to be the evangelical/Baptist "accepting Jesus as my Savior" kind of profession of faith, and I take Wallis to be acknowledging that it is needed. Then, in supposed agreement with Bonhoeffer, he says that to this must be added acts of obedience. The problem I have with this, theologically, is that it amounts to cheap grace plus works of the law with no inidication of what it is that this latter was necessary for other than congruency.

The genius of Bonhoeffer is precisely in his presentation of obedience to Christ as the very susbtance of faith, not something done in addition to it. It is precisely as God is redeeming in Christ the world that we are called to take up the yoke of Christ. In this regard, Bonhoeffer cites Matthew 11:28-30 ("Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.") at the end of his introduction to Discipleship.

So, to be clear, the issue I have with Jim Wallis is not with his cause. I support his cause and I thank God for calling him to this work. This issue I have, increasingly, is with his presentation, which far too often draws on the clumsy tool of Law where it could invoke the power of the Gospel.

Sunday, February 05, 2006

Three Gems

Three gems from the introduction of Abraham Heschel's The Prophets:

Conventional seeing, operating as it does with patterns and coherences, is a way of seeing the present in the past tense. Insight is an attempt to think in the present.

To comprehend what phenomena are, it is important to suspend judgment and think in dettachment; to comprehend what phenomena mean, it is necessary to suspend indifference and be involved.

Thought is like touch, comprehending by being comprehended.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)